Long before the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic began their spread across the globe, the two halves of Austin divided by Interstate 35 were already riven by two strikingly different public health realities.

A commonly known but often ignored fact of life in Austin for decades – the difference in health outcomes for those living East Austin and West Austin — is under the magnifying glass as the COVID pandemic sweeps through the city.

Now as several states, including Texas, reel from a resurgence of the virus triggered by our disregard for the basics of prevention, caution, and collective action amid a rush to reopen, Texas stands among the global epicenters of the pandemic.

On July 7th, daily cases in Texas increased by 10,000 for the first time, an upward trend that continues to accelerate. Italy, a country with roughly twice the population of Texas, never experienced a jump of more than 7,000 cases in any 24 hour period despite the nation’s own weeks as the global epicenter earlier this spring.

Austin, in particular, suffers a higher positivity rate – the percentage of positives among all being tested — than any other city in a country stricken with more cases than any other on the planet. Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio also hold the lamentable distinction of landing in the top 5 American cities for positivity rate – a stark testimony to the calamity that is engulfing Texas.

As deadly as the virus is, the numbers reveal that it is much more lethal for those who are Black, brown, or live in a neighborhood like Austin’s East Side, an example of America’s continued scourge of segregated cities.

Of those testing positive for the coronavirus in metropolitan Austin, 59 percent are Hispanic. And Hispanics have a 24 percent positive testing rate, the highest among any group, according to data released by Travis County. But only 33.6% of Travis County residents are Hispanic, according to US census data.

Austin and surrounding cities can expect hospitals to be overwhelmed in days and the city’s eastern half is suffering as never before. And it comes, of course, amid the storm within a storm.

The uprising against police brutality that began with the Memorial Day killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, soon spreading to the rest of the United States and beyond, underscores the inequality faced by communities of color and reaches far beyond healthcare to all aspects of life. In Austin, the fulcrum of the protests was on or near I-35, as demonstrators spot lit the historical boundary between justice and injustice.

Segregation in Austin

Austin’s history of segregation, deliberately racial and consequently economic, is well documented.

That history traces from the 1928 ‘Koch and Fowler Plan’ that created a designated “Negro District,” outside of which Black residents were denied city services, to New Deal-era redlining that excluded minority groups from many of the benefits intended to rescue households from the Great Depression, and finally to the modern era during which Interstate 35 was deliberately placed to serve as a clear divide between wealth and race.

Austin continues to struggle with segregation, and minority groups continue to disproportionately suffer as a result. Austin ranked as the most segregated American city with a population of at least 1 million people, and third among all metro areas behind only Tallahassee, Florida and Trenton, New Jersey, in a study in 2015 by Richard Florida at the University of Toronto.

A similar 2017 study funded by the Urban Institute found that of the 100 most populous “commuting zones” in the United States, Austin was the 13th most segregated zone in 1990, fell to the 25th most segregated zone in 2000, but again rose to becomes the 18th most segregated zone by 2010.

In a 2018 article by the Austin American-Statesman, sociologist John Logan of Brown University mentioned research that placed Austin as the 17th most segregated major American city between 2010 and 2014. While stopping short of classifying Austin as one of the worst cases of segregation in the country, Brown told the Statesman, “The general point is that all U.S. metro areas are highly segregated by income, and that has consequences for the lives of residents.”

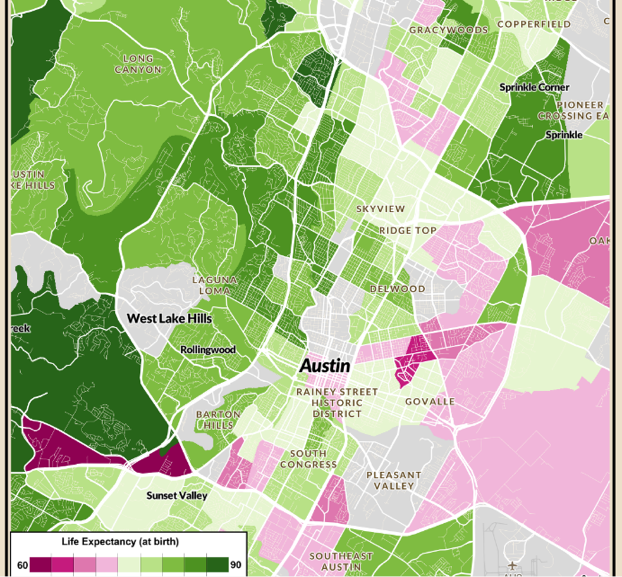

What are those consequences? Unfortunately, those living in disadvantaged areas of East Austin are expected to live only about 80 percent as long as those living in West Austin, according to new research from the Episcopal Health Foundation.

Full interactive map – visit the Episcopal Health Foundation

The difference between the life expectancy of some higher income areas of Austin, such as the area around West Lake Hills (85.2 to 88.9 years), and some of the lower income areas, such as Chestnut and Govalle (71.9 to 74.1 years), is roughly the same as the difference between Hong Kong, with the world’s highest life expectancy at about 84.7 years and that of Pakistan, which places 138th globally.

Clearly, the differences between West Lake Hills and Chestnut are not the same as those between Hong Kong and Pakistan, so what is going on? How can these areas just seven miles away and a 20-minute drive by car have such disparate life expectancies?

Poverty and Life Expectancy

The most obvious place to start is with the income differences between residents living in these two sections of the same city. Unsurprisingly, when it comes to healthcare, income status will overwhelmingly determine how long an individual is expected to live.

On a national level, the gap in life expectancy between the richest American men and the poorest American men was roughly 15 years, as revealed in a 2016 study by Harvard university. That study noted that the difference is about the same as the life expectancy gap between the United States and Sudan. The gap meanwhile between the richest American women and the poorest was roughly 10 years – roughly the difference in life expectancy between those who smoke cigarettes and those who do not, the same study notes.

Further, the study determined that this life expectancy gap between high- and low-income Americans is growing. Between 2001 and 2014, life expectancy for the wealthiest Americans increased by three years on average, while life expectancy for the poorest Americans remained unchanged.

When we zoom into Texas, these statistics become even more alarming. Texas finishes 34th out of the 50 states, according to the United Health Foundation’s composite health measure America’s Health Rankings. And according to the Episcopal Health Foundation, Texas ranks 50th out of 50 states in the percentage of persons without health insurance, with 17 percent of Texans living without health insurance, compared to a national average of 9 percent.

Some 34.8 percent of all Texans are classified as obese, 37.97 percent of all Hispanic Texans are obese and 40 percent of all Non-Hispanic Black Texans are obese, according to the Center for Disease Control. Although Texas has a lower infant mortality rate than the U.S. average (5.8 deaths per 1,000 live births compared to a national average of six), Black Texans experience a rate of double (10.8 deaths per live births) that of White Texans (5.2 deaths per 1,000 live births).

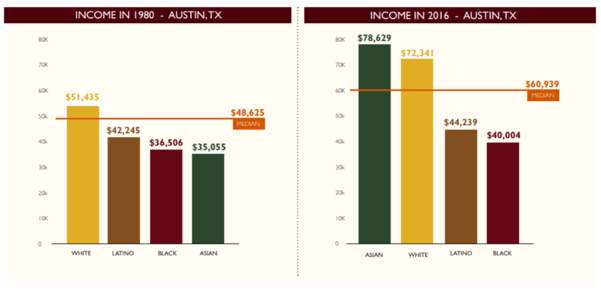

These disparities are clearly divided among race, though they are driven by poverty. Median income in Austin has risen in the past 30 years. Not all groups, however, have shared in that growth.

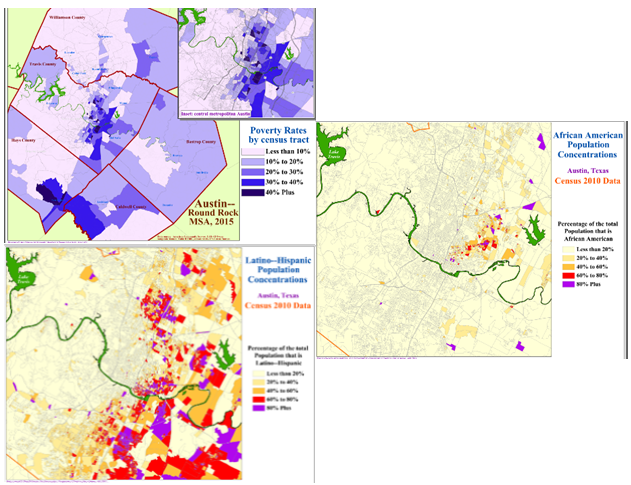

Black and Latino Austinites remain very much segregated to the parts of the city east of Interstate 35, and as demonstrated by the maps below – it is a distribution that correlates closely with that of poverty.

Access to Care

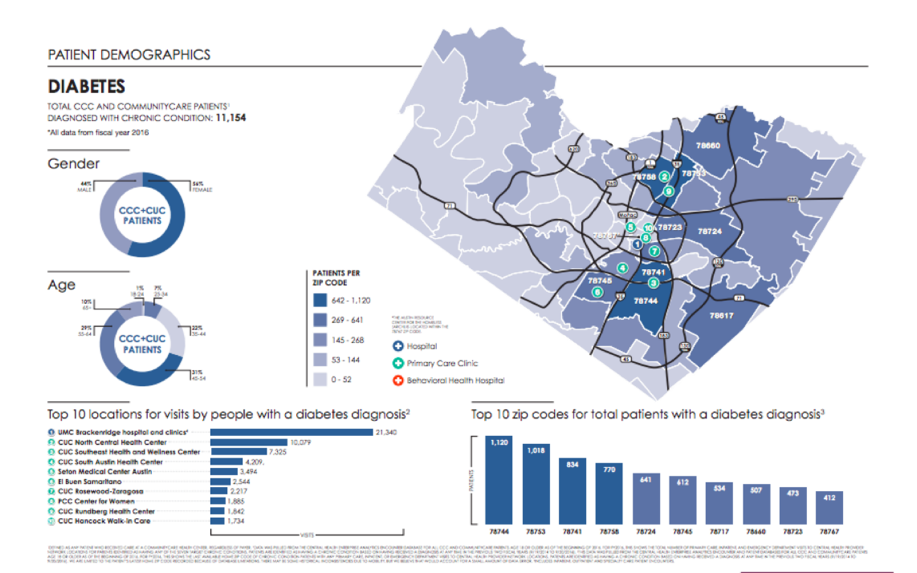

Adults that are diagnosed with diabetes can expect to live on average 15 years shorter than the average, according to the Mari Gallagher Research and Consulting Group. In Austin, diabetes cases are overwhelmingly present on the east side of Interstate 35, as shown in the 2017 map below from the Central Health Demographic Health Report.

In sharp contrast, the areas that have the highest rates of diabetes, are also the areas of the city that tend to not have healthcare facilities present. The map below, which I generated using Google Maps, shows the locations of the major hospitals, clinics, and community health centers throughout central Austin.

Food Deserts

Another major determinant of health outcomes, seemingly obvious but often overlooked, is the availability an individual has to basic nutrition. Food insecurity, the experience in which individuals or a community have inconsistent access to basic nutritional resources, is an ongoing problem in the United States. One in six Americans suffer from food insecurity, either because they lack the funds necessary to purchase quality food, or because they live in a food desert, reported Duke University in a 2017 paper.

A so-called “food desert” is defined as a segment of the country that lacks access to affordable fresh vegetables, fruit, and other basic foods of full nutritional value, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And 23.5 million Americans live in a food desert. By contrast, wealthy areas of American cities can expect to have 3 times the number of grocery stores than lower income areas, and predominantly White areas can expect 4 times the number of grocery stores than predominantly Black neighborhoods, according to a study published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

In Austin, these numbers are worse.

One in every four people living in Austin is food insecure, over 427,000 people live over a half mile away from a grocery store, and over 247,000 people live in what can be categorized as a food desert, overwhelmingly in lower income areas of East and South Austin, according to a 2016 study from the LBJ School of Public Affairs. A quick search on Google Maps for a grocery store in Austin reveals that the Interstate 35 barrier is the clear divide.

Exacerbating the problem, is that once an area of a city becomes a food desert, it enters a vicious socioeconomic cycle. People living within a food desert can expect to live a shorter life, but they also tend to witness their wealth continue to decrease over time. As wealth leaves these areas, new businesses (including, but not limited to, grocery stores) are less likely to open.

The effects of living in a food desert on that area’s population can be devastating. The lack of access to affordable and quality food are shown to raise the risk of chronic illnesses such as diabetes and obesity (as we have already discussed), but also cardiovascular diseases, as many residents of these areas are forced to get their nutrition primarily from fast food restaurants and other sources of poor nutrition.

Education

Finally, it is necessary to stress the importance of the access to quality education on quality health outcomes. Generally, more education will lead to more gainful employment, a family’s increased ability to spend on healthier foods, more convenient transportation options, and allow more time to spend on exercise.

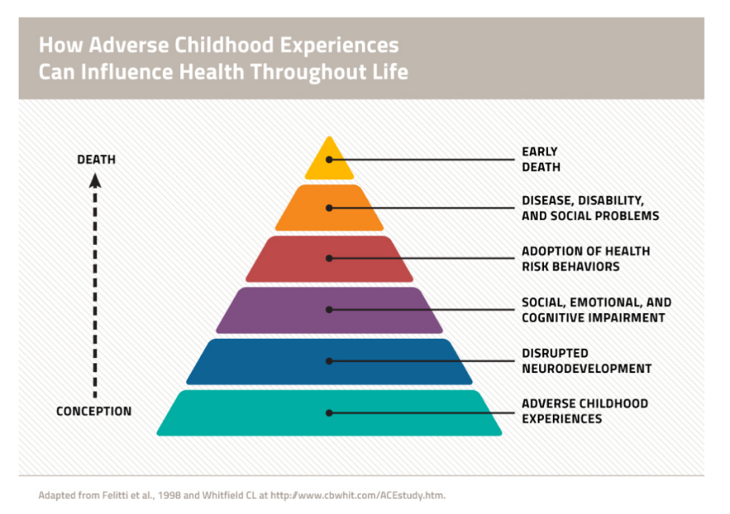

The more time that children spend in school, the more likely they are to improve their social skills, their ability to cope with psychological stress, and to have the tools to navigate a complex world of healthcare. The relationship between healthcare and education represents an example of reverse causality as well – students who struggle with poor health and stress in early life are less likely to succeed in an educational environment.

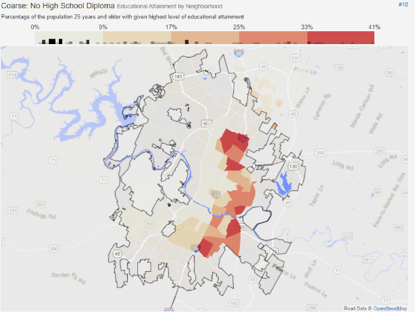

Unfortunately, once again, access to quality education is not equitable in Austin. According to 2018 maps from Statistical Atlas, Interstate 35 tell us the story with clarity.

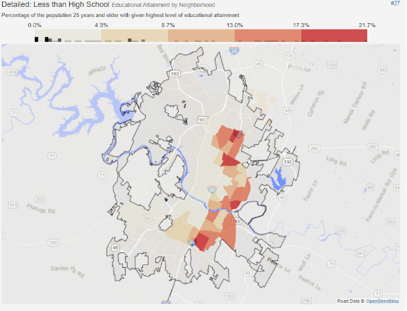

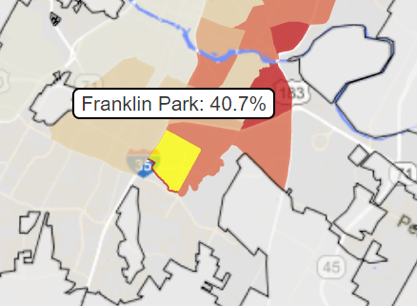

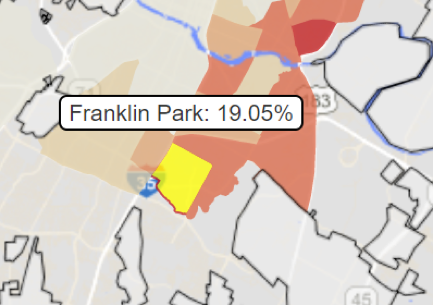

First, the map below on the left shows each Austin neighborhood, colored by the percentage of residents that did not complete their high school education. The map on the right is colored by the percentage of residents that did not even attend high school.

In the Franklin Park neighborhood (commonly referred to as Dove Springs), 40.7 percent of residents were reported as having less than a high school diploma, and 19.05 percent of residents never attended high school. Franklin Park is part of the 78744 zip code, the part of the city with the highest rate of diabetes.

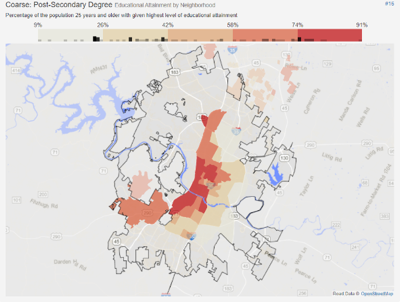

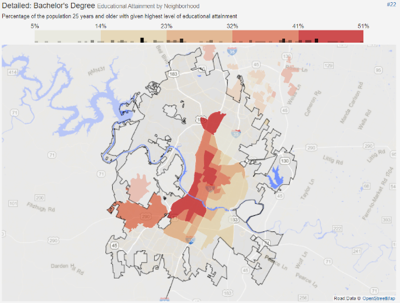

The map below on the left shows Austin by neighborhood, colored by percentage of residents that completed at least some form of post-secondary degree. The map on the right shows Austin by neighborhood, colored by percentage of residents that completed at least a bachelor’s degree.

Clearly, educational outcomes are centered firmly on the higher-income areas of Austin. The same parts of the city with lower levels of diabetes and other chronic diseases, with more access to quality healthcare and nutrition, and consequently, a much higher life expectancy under “normal” circumstances.

COVID-19

These blatant inequalities set the stage for the reckoning that is the COVID-19 pandemic. Generations of racist policies and discriminatory practices left a large segment of Austin’s population ripe for tragedy, and now that tragedy is upon them.

Those living in the 78744 zip code – the area including Franklin Park / Dove Springs – and other similarly marginalized parts of Austin are feeling these effects of the disease at least as acutely, if not more, as anywhere else in the United States, perhaps in the world.

Again, in all of Travis County, Hispanic residents are demonstrating a 24% positive testing rate for the coronavirus.

Carmen Llanes Pulido – Executive Director at local non-profit Go Austin / Vamos! Austin – paints a picture even more grim.

“The positivity rate in Travis County for Latinx residents might be around one out of four for all of Travis County, but in some of these areas [not only Franklin Park / Dove Springs, but the entire Eastern Crescent], the rate is actually closer to 40 percent,” Pulido said.

Why and how is this happening? How are Hispanics in these communities testing positive at a rate of approximately four in 10 while the national average is closer to eight in 100?

“Those living in these communities are hit with this virus in a five-pronged manner that puts them at grave risk,” Pulido said “The five prongs of this are – 1.) Higher exposure, 2.) Higher proximity to infections, 3.) Higher risk of serious complications due to pre-existing co-morbidities, 4.) Systematic oppression that limits resource access, and 5.) A high allostatic load under “normal” circumstances exacerbated by the crisis. This is simply death by a thousand cuts.”

Let us go through Pulido’s five prongs in greater detail:

1.) Exposure – These communities are populated with a high number of essential workers, who naturally through their need to continue to go to work as normal and who often work in environments in close proximity to other workers, are disproportionately exposed to the virus. In Dallas, as many as 83 percent of all hospitalizations are workers associated with critical infrastructure.

Essential workers, especially those vulnerable by their uncertain immigration status, are often forced to work even if they’re sick, cannot afford to miss work even if their employer grants them the time off, or are certain their employment will be terminated if they test positive for the virus.

“Many people, their boss already told them, if they get tested for the virus and the result is positive, then they are going to get fired. They cannot take the risk of a positive test or missing work because their job hangs in the balance,” said Susana Almanza, environmental activist and director of East Austin organization PODER (People Organized in Defense of Earth and her Resources).

2.) Proximity to Infections – Although the workplace is a common source of rampant spread of the virus, the household is even more central to the rapid distribution of the virus, especially in homes where quarantining infected members of the family is difficult, if not impossible.

In Franklin Park / Dove Springs, it is not uncommon for not only multiple families, but multiple generations of multiple families, to all occupy the same single-family home. Under “normal” circumstances, because of the need to pool resources and stretch dollars, this type of arrangement makes a lot of sense and is often the only way of getting by.Under the circumstances created by the pandemic, it is a recipe for disaster.

“If you are sharing a bedroom, two or three people to a room, or multiple families sharing one bathroom, there is no such thing as isolation,” said Almanza. “Most everyone I know in these areas are living multiple families to a home. Isolation is not real, quarantine within the home is not a reality, and there is no alternative.”

3.) Pre-Existing Conditions and Co-Morbidities – Described at length above, communities such as Franklin Park / Dove Springs demonstrate higher rates of diabetes, heart conditions, obesity, and other chronic ailments, making them at much higher risk for the death or serious illness as a result of the coronavirus.

These communities are food deserts under “normal” circumstances, but amid the panic buying in the early stages of the pandemic, and the limited food options made available to them through donations and other efforts, this concern is exacerbated.

“The fact is that the food available is limited, and what we can access tends to be canned goods. Not healthy and not sufficient for the needs of a family,” said Almanza.

4.) Systematic Oppression – Austin’s long and complicated history of racial segregation, gentrification, and unequal distribution of critical infrastructure – most critically healthcare centers – leave people in these communities without access to what they need to survive this pandemic.

Further, with high rates of uninsured, underinsured, and most frightful of all, completely undocumented persons, many would not even be able to use these resources if they did exist or if they were able to reach them. There is little, and more often than not, no safety net for people if they lose their income, housing, or especially, their health.

5.) Allostatic Loads – A term meaning the wear and tear on the body, “Allostatic load” refers to the accumulated effects of stress on health. Poverty is stressful.Life for those in these communities is difficult, and the pressures on every individual are immense, again even under “normal” circumstances. Often the most effective way of countering these stresses is through the closeness of the community and the ability of people to effectively organize, share resources, and help each other out when needed. This pandemic pushed people apart from each other in ways that go beyond just the physical, and as the death toll inevitably continues to rise, communities will continue to lose beloved and central figures.

“This is happening. People are getting sick. I now know of four people who have lost at least one of their parents, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain the community stability needed to survive, despite remarkable efforts from people here to maintain our cohesion” said Pulido.

So, what does a person go through if they live in Franklin Park if they believe they might have contracted the coronavirus? How are these concerns applied in reality?

Let us go through a brief exercise in the first person.

I want to acknowledge that I do not speak for anyone in these communities, nor is this a lived experience for me personally. However, I believe that it is important to put these issues of policy, history, and inequality into a voice for more simplified yet poignant – and this was constructed strictly through careful research and testimony from community activists.

“Oh no, I’m starting to feel ill. What am I going to do about missing work? My financial contributions to the household are essential. What if my boss refuses to give me time off? What if I get fired? How will I find another job, and when will that be possible?”

“How am I going to quarantine myself from my family? With many of us living together, how can I make sure to keep the elderly safe? What about taking care of my children? What do we do if more than one of us starts to get sick? My mother – she is diabetic. I know that is a problem. My father – he has a heart condition.”

“Where do I go? The health clinic off Montopolis? They are not taking appointments; do I need to go to St. James on I-35? I do not have insurance. How much will this cost? Can I really trust the hospital? What if the hospitals are where people really get sick? My sister – she is undocumented, what if they find out because I go in for a test? What does a positive test mean? Will my boss find out?”

Finally, it is important to recognize that as it widens gaps in education during this pandemic, the digital divide represents a significant barrier to seeking the necessary information, tests, and treatments.

In order to make an appointment to get a coronavirus test, it is necessary to use an email address and access either a smartphone or a computer, modern conveniences that many Austinites may take for granted but are much less available in the most at-risk communities. This is especially problematic for the elderly members of the community, who even if they can access these technologies, often are unable to use them properly.

“The digital divide is very real for these communities, and its causing a lot of glitches that prevent people from getting the tests that they need. Since many people do not have an email address, we are having to constantly create new ones just so that they can attempt to get a test. And the problems ahead as a result of the lack of access to the proper tech – such as effective contact tracing – do not seem plausible,” said Almanza.

Conclusions

As we can see, the fact that the terrible effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are felt more deeply by Austin’s communities of color on the East Side should come as little to no surprise – and the fact that little to nothing has been done to address these chasms in care will be perhaps the defining stain left by this public health catastrophe.

In an attempt to find a bright side, we can recognize that sometimes it takes disaster to learn a lesson and there is opportunity in crisis. The immediacy of the coronavirus threat is presenting Austin with a crucial moment to close some long-ignored gaps between East and West and emerge a stronger city after the pandemic.

“There is a lot the city can do. Providing hotel rooms for members of this community to isolate themselves from their families, making the 311 coronavirus hot line 24 hours a day to accommodate the varied schedules of essential workers, improving access to personal protective equipment, masks, hand sanitizer and other supplies, and bringing testing to these communities would be a start,” said Almanza.

The time is now, when the need is at its greatest. Austin’s legacy beyond this pandemic will be defined very simply by the way it cares for its most vulnerable, and Austin’s more equitable future must begin now.

If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.