Photo: Christopher Brown

In the middle of this summer’s second wave COVID-19 outbreak, the Chamber of Commerce boosters of Austin, Travis County and Del Valle pulled a pandemic hat trick: closing a deal with Tesla to build a new plant east of town for the production of the company’s Texapocalypse-ready Cybertrucks and Model Y SUV.

In a metropolitan area where rapid growth over the past decades produced some of the worst economic segregation in America, the construction of a $1.1 billion “Gigafactory” that will create 5,000 diverse new clean energy jobs and a wide range of collateral economic benefits is good news—especially amid the economic crisis of prolonged quarantine and unemployment.

The site’s location, on the banks of the Colorado River just east of SH-130, provides the community with an opportunity that has gotten less attention: a chance to plan for the future preservation of one of Austin’s greatest and most under-appreciated ecological and recreational resources.

Lady Bird Lake is the natural park that defines downtown Austin, and Lake Austin and Lake Travis are the core attractions around which the county’s more affluent residential neighborhoods have exploded since the construction of Longhorn Dam in 1960. But east of Pleasant Valley Road, below the dam, the river follows its natural channel. The zoning of industrial land uses along the river corridor has deterred most other forms of development since World War II, managing to maintain a riverine greenbelt all the way to the county line and provide urban habitat for all manner of wildlife. Little used by anyone other than fishermen and paddlers, to get out on the urban Colorado is to escape from the city without leaving it, in a place that preserves the memory of what this beautiful spot on Earth was like before the founding of “Waterloo.” But as development attention shifts east, this precious resource could quickly be ruined unless the community provides a vision for its preservation.

The unsung activism behind thoughtful planning for Lady Bird Lake

Few Austin residents know how much planning and community activism it took to achieve the currently tranquil character of Lady Bird Lake, where motorboats were once allowed and the annual Aqua Fest brought something like F1 on the water—and right up into the backyards of residents of East Austin. Development along Town Lake was relatively unrestricted, until the construction of the Hyatt Hotel next to Auditorium Shores in 1984 provoked an uproar that culminated in the 1989 adoption of the Waterfront Overlay—a thoughtful approach to planning that divided the riverfront into quadrants in which development parameters were tailored based on the very different conditions downtown, west of Lamar to Mansfield Dam, east of Interstate-35 to the Longhorn Dam, and from the Longhorn Dam to 183.

The Waterfront Overlay drew from a detailed 1985 Town Lake Corridor Study that inventoried existing uses and ecological resources. The section on the river below Longhorn Dam captured something rare in any city:

“The Colorado River and its environs… are very different in character from the upstream dammed segment and its highly urbanized environment. The aesthetic quality of the river corridor is best described as pastoral, tranquil. The scene is that of the Colorado River in early days: gravel and sand bars, shallower waters easily fished by many species of water fowl and other birds, e.g., osprey, bald eagles and peregrine falcons and beds of submerged aquatic plants, and ashes, willows and anacuas. Although Highway 183 noises dominate the soundscape of the far eastern boundary, even there the river is quite lovely and peaceful.”

Through the efforts of the city and community activists, those conditions have mostly been maintained to the present day. The generosity of Roberta Crenshaw and the leadership of neighbors and city planners led to the conservation of almost 400 acres on the south bank and the creation of Roy Guerrero Park, an urban green bigger than Zilker Park that is among the city’s most popular birding destinations and home to the no-longer-so-secret “Secret Beach.” Across the river, another gift endowed the 47-acre Colorado River Wildlife Preserve tucked in under the Montopolis Bridge, and the Waterfront Overlay has guided compatible redevelopment in an area slowly transitioning from industrial uses to office space and hospitality along East Cesar Chavez.

But east of 183, those rules end. The dominant land use on both sides of the river below the Montopolis Bridge is mineral extraction, and every morning even during quarantine you can see the big trucks loaded with aggregate dredged from the ancient floodplain being hauled to build the new skyscrapers and roads of the fastest growing city in America. And if you paddle downstream from the Montopolis Bridge you will soon see the first of the new suburban subdivisions built so close to the river some of the houses already look like they are about to slide off the bluff and into the water, only a few years after construction.

the Colorado River, mineral extraction on both sides of the

river is slowing giving way to new subdivisions.

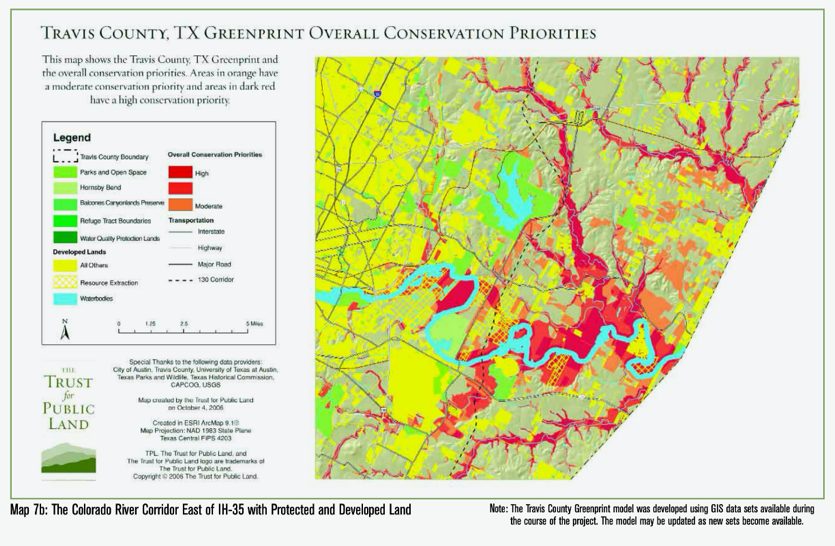

More than a decade ago, the Trust for Public Land in coordination with municipal and county governments from around the region published the 2006 Travis County Greenprint and 2009 Central Texas Greenprint, which identified high priority lands for future public acquisition or conservation, heavily concentrated along the river. Their timing at the peak of the 2007-09 financial crisis was not optimal. But the City of Austin’s Parks and Recreation Department has done an impressive job of executing on its part of the plan, acquiring a network of new riverfront parklands including the John Treviño Metropolitan Park now in development, the more recently acquired Bolm Road District Park site between the river and 183 on the site of a former gravel pit, and the Walnut Creek hike and bike trail that follows old railroad right of way along the path of that historic Colorado River tributary from Govalle Park to Decker Lake.

On the south side of the river, in the zone shared with Austin-Bergstrom International Airport and Circuit of the Americas, the developments currently on the boards are more commercial, but mostly at a healthy distance from the riverbank. Closer to town, much heavier development pressure is in play along Longhorn Dam, as Oracle builds the second phase of its 1990s-style cloud factory on Lakeshore Drive on a site where a more visionary city might have put a museum or other civic use, and the City just authorized the plowing of a new road through the southwest corner of Guerrero Park to facilitate the higher-density “Domain on Riverside.”

The site of the Tesla factory is one of those old mineral extraction sites—a 2,100-acre sand and gravel quarry that Martin Marietta Materials picked up in 2014 in its acquisition of Texas Industries. In the fall of 2018, a new affiliate of MG Realty Investments and Momark Development announced plans to build 12,000 new homes and 2 million square feet of commercial space on that site—a town center aligned with the Imagine Austin plan that would be called “Austin Green” and also include 700 acres of public parks and open space. Tesla plans to continue the parkland plans, with Elon Musk showing he gets it:

“We are going to make it a factory that is going to be stunning. It is right on the Colorado River. So we are actually going to have a boardwalk where there will be a hike and biking trail. It is basically going to be an ecological paradise—birds in the trees, butterflies, fish in the stream. And it will be open to the public as well, so not closed and only open to Tesla.”

A powerful precedent for development along the banks of the Colorado

If Musk’s vision of a green factory is realized, it will provide a powerful precedent for other new developments along the urban and exurban Colorado. But to guide the future of the river corridor as other developers follow Tesla’s lead, city and county leaders should grab the opportunity to outline parameters designed to maintain the beauty of the river and its wild banks in a way that will at the same time facilitate compatible redevelopment and the transition from rural to urban uses. Something as simple as a baseline setback from the river could be all it really takes. That’s the main component of the Waterfront Overlay that applies west of 183, along with height and impervious cover limits. In the longer term, it could include plans for the phase-out of riverfront mineral extraction. It needn’t require any major expenditure of public funds: the Shoal Creek Conservancy has demonstrated how conservation and redevelopment along an urban waterway can be optimally coordinated, with developers helping to fund restoration and maintenance of ecologically valuable zones impacted by their construction. In partnership with the City of Austin’s Parks and Recreation Department, East Austin-based environmental and community action group PODER (People Organized in Defense of Earth and Her Resources) is organizing a coalition of stakeholders to advocate for such a vision, with the aim of adapting that model of public-private partnership to conservation of the Colorado River corridor below Longhorn Dam, beginning with a strategic plan that could provide an excellent starting point for more comprehensive riverfront planning efforts.

The site of Tesla’s new factory is the heart of historic Austin—a stone’s throw from the sites of the multi-racial colony of Webberville and the original settlements by pioneers like Ruben Hornsby and Josiah Wilbarger, and downriver from the main water crossings of the Chisholm Trail.

At Hornsby Bend, just across SH-130, the city has one of its greatest ecological assets, a riparian woodland that is one of the best birding sites in the region. Part of the genius of Austin, and one of the things that makes it such a livable city, is the visionary work that has gone into preserving a network of wild green spaces throughout the metropolis. Tesla’s new project provides us the opportunity to extend that vision east, along the river corridor that is Austin’s most valuable natural asset.

In an age when great cities like Munich, Los Angeles and Houston are spending hundreds of millions of dollars to restore their industrialized urban rivers to a more natural condition, Austin is blessed with a stretch of essentially wild river that has managed to survive more or less intact, mostly through the accidental preservation of industrial downzoning (which was no accident from the planners’ perspective—the product of Jim Crow-era racism). With a little bit of planning and leadership, we can make sure we don’t go in the other direction, and provide a vision that encourages compatible redevelopment while maintaining this precious asset for future generations.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.

An excellent overview of a critical imperative for preservation of the few wild areas left in the urban environment.

Very thoughtful and well written piece.

Thanks.

WB