Photo: U.S. Library of Congress

Review: The Sword and the Shield – The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., by Peniel E. Joseph, 2020, 373 pp., Basic Books

As much of America struggles to confront the legacy of racism so symbolically captured in the May killing of George Floyd, through nightly protests and an explosion of anti-racist initiatives, it is hardly a foregone conclusion that – this time – we will get it right. Which is why a timely new book examining just how we failed the last great moment of racial reckoning a half century ago, and then convinced ourselves it was a success, is a primer for this moment.

“In many ways, racial segregation in America has worsened since” the hallowed civil rights victories of the 1960s, argues historian Peniel E. Joseph in The Sword and the Shield – The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. “National progress has been stalled, indeed reversed, by local, state, and federal policies – from gentrification and zoning laws to tax codes – that have made dreams of racial integration as distant as an unseen horizon.”

One way to expose this reality is in the numbers, as a pandemic has so ruthlessly done. Along the spectrum of indicators, from infant mortality to educational success to incarceration rates, wealth and, of course, treatment at the hands of police, the divides between Black, White and brown America have become chasms. But another way to examine this failure, the means of The Sword and the Shield, is to chronicle how we’ve mythologized much of that failure away. Yes, overt and interpersonal racism is not tolerated in most quarters. The worst of Jim Crow discrimination has been eliminated, and people of color now people every institution – sometimes at the top. But despite pinnacles of success that include the election of a Black president, it is a sanitized version of the “heroic period” of the civil rights era that we’ve memorized, Joseph argues. The 20th Century was anything but a “seamless march toward racial progress.” And if we are to get to that “unseen horizon” to which he alludes, it’s a history that we need to relearn. His book is a good place to start. All the more so here in Austin, a city with its own legacy of shame, an ironic microcosm of a nation’s superficial liberalism yoked to whiteness.

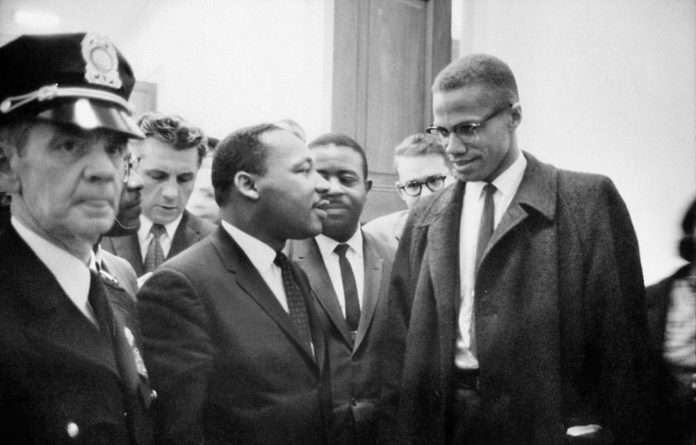

The metaphors of the title represent the Janus-faced way we remember the two leaders, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. King we remember as the insider who spoke to the corridors of power, a man whose “shield prevented a blood-soaked era from being even more violent.” Malcolm, meanwhile, is recalled as the renegade speaking to the urban street corners, wielding his “sword in pursuit of black dignity.”

This superficial myth of the two men as opposites, enshrined in iconography from a national holiday to postage stamps to Pulitzer Prize winning biographies and award-winning movies, requires “taking them down from the lofty heights of sainthood and rescuing both of these men from the suffocating mythology that surrounds them,” writes Joseph.

The backdrop reality to the work of Joseph, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and founder of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy, is our larger era of new historiography. The edifices of historic triumphalism don’t suddenly collapse. The essential truth of how we broadly understand so much of our history is the ubiquity of falsehood. Or certainly much left incomplete.

The durable lattices of interwoven myth-making

The reasons for this undergrowth of myth shrouding the history of America’s four centuries of slavery and profound injustice are sometime nefarious, sometimes not. But they are always complex. The inherited epics that comprise our sense of self and society are never built of simple storylines. Rather, they are constructed of durable lattices of interwoven narratives. They are built over decades by multiple authors with diverse interests. They reach us through schoolbooks approved by politicians and iconic films appealing to market passions. News of them is hastily crafted, often by reporters with borrowed scripts which they truncate further. And old recollections of even older glory, war stories told on back porches, are selected and shared carefully. Once combined and hardened in common memory, these stories do not yield easily.

Which is why a history as twisted, tortured and capriciously imbedded in national consciousness as race and racism in America can only be disassembled and remade brick by brick. And so we are doing, however painfully and late.

Recent decades have brought us uncomfortable truths about Thomas Jefferson’s DNA and his notions of just what in fact did constitute “created equal.” We’ve learned that George Washington’s “false” teeth were not fake or wooden after all; they were actually quite real, and probably extracted from his slaves. Just a year ago, the New York Times Magazine brought us the “1619 Project,” rolling back the legacy of slavery to its origins a century and a half before the sunnier story of an inconvenient institution simply inherited by the founding fathers in 1776. And even that work, which won the Pulitzer Prize, has been challenged by other scholars who note its English-centrism. Yes, the first slaves to English America arrived in 1619 in Jamestown, but the Spanish brought slaves to what is today’s Florida coast a half century earlier, in 1565.

Today we remember, even venerate, the public sacrifices made in the civil rights era: the beatings in the street, the humiliations at lunch counters, the stoic children defying segregation under the eyes of federal troops, the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till and so many others. And we should. But the private and hidden terrors, the gratuitous destruction of Black identity and dignity by doormen, teachers, employers, store clerks, doctors, nurses, clergy and so many others, those who created in author James Baldwin’s words, “a state of mind in which, having long ago learned to expect the worst, one finds it very easy to believe the worst,” is a reality of the era scarcely acknowledged. Then and now. And King and Malcolm both bravely, if often in different ways, confronted this facet of racism with no less vigor than with their marches, boycotts and standoffs, a history which The Sword and the Shield demands we acknowledge.

It’s a messy business this coming to terms. But this larger mirror of our history being fashioned by a new generation of scholarship refracts so much new upon the conventions and institutions of today, providing new insights into realms from professional sports and their player-owner structures to the freeways encumbering traffic because they were designed around old plantation boundaries.

The edifice of the Confederate “Lost Cause” has been fraying for a while. But it is only in the wake of Floyd’s brutal killing in Minneapolis, with all that has ensued amid a pandemic, that it at last truly fractured. More than a few statues celebrating a deeply flawed version of the Civil War, tales in stone created decades after the war was actually fought, have been toppled. Mississippi finally surrendered its rebel battle flag, the last southern state to do so.

New blocks of narrative building are brought in alongside those bricks set in new contexts. While some idols, Gen. Robert E. Lee for example, are getting a long overdue reposition in our collective imagination, other figures are being invited into it for the first time. Cathay Williams, a freed slave and the only woman to have served in the legendary Buffalo Soldiers, is just one example of a heroine newly rescued from almost complete obscurity.

Still, it’s a complicated moment. While Twitter mobs stalk and pollute the discourse at its basest plane, vicious intellectual combat over the history of race in America plays out in the high echelons of academic scholarship as well.

A movement robbed of its truly global nature

And it is into this fraught moment of historical disentanglement that historian Joseph has courageously arrived with an examination of the civil rights movement itself, published just at the end of March. Peniel’s is a bold look at how the so-called “heroic period” between the 1954 Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education ruling and the 1964 passage of the Civil Rights Act too has been debased in the retelling – and needs to be repositioned.

That movement, argues The Sword and the Shield, has been robbed by the mechanisms of narrative sanitization of its truly global nature, its connection to issues of unfettered capitalism and, not least, of the full views, actions and motives of the movement’s two leading protagonists, Malcolm and King.

The lessons of this book are broader than just King and Malcolm. Joseph charts the thick if indirect line that begins in the early 20th Century with Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican publisher, and author W.E.B. Du Bois, who both sought to unify people of African descent worldwide. That line moves through the missed opportunities for integration immediately after World War II, up through the “heroic period” and on beyond the deaths of King and Malcolm to the Black Power movement of the 1970s that Malcolm inspired, both through his work with the Nation of Islam and after his famous break with the organization as well. It then continues up to much occurring since, through the election of Barack Obama, the birth of Black Lives Matter, and on through both the legacy and recent activism of the last lion of the civil rights movement, Rep. John Lewis, who died last month and whose eulogies still echo in our ears.

Joseph also does not neglect the large pantheon of so many contemporaries of the era. These include the less-remembered activists Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown and Bayard Rustin; the more remembered such as Andrew Young and Julian Bond; and, the pioneering journalists and writers who loomed large across the era, Baldwin, Louis Lomax, Alex Haley and Langston Hughes to name just a few.

But the two main protagonists are the exemplars of this now-diminished history and the leitmotif throughout is how we misremember both. Malcolm, assassinated in 1965, is seen retrospectively as the radical Black nationalist who favored separation to integration, while in fact he was far more interested in dialogue and White-Black reconciliation than acknowledged. Our view today of King, assassinated three years after Malcolm, is meanwhile framed by a few selective quotes from the March on Washington, in particular his “dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” That speech, of course, was and is monumental, but it “also remains one of the most misunderstood addresses in American history,” as we now have excised much of it that was revolutionary from any recounting, argues The Sword and the Shield.

“In popular culture they represent opposing visions of racial equality; where King dreamed of carving a stone of hope from a mountain of racial despair, Malcolm forcefully identified a growing nightmare of racial injustice, Jim Crow segregation, and simmering rage,” Joseph writes. “This neat juxtaposition obscures more than it reveals, erasing the profound ways in which their politics and activism overlapped and intersected.”

The larger context of erased history for Joseph is the international backdrop of the Cold War, the anti-US movements and the anti-colonial struggles that raged across Africa, Latin America and Asia at the time of the civil rights movement. In 1957, when President Dwight Eisenhower was still refusing the upstart civil rights leader a White House meeting, King traveled to India and was accorded the full honors of a visiting head of state by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. When Cuba’s new president Fidel Castro attended a United Nations session in New York in 1960, he stayed in Harlem and met with Malcolm.

When King wrote his less quoted “Letter from Birmingham Jail” after his arrest in that city in 1963, he very expressly identified the Black freedom struggle as part of a much larger global movement. “He defined citizenship transnationally, comparing the slow pace of racial justice in America to the ‘jet-like speed’ of African and Asian nations hurtling toward independence and political self-determination.” Joseph notes he also, sounding more like Malcolm than the King we recall today, repudiated “white Americans – from the clergy to ordinary citizens – unable to empathize with the pain of racial injustice.”

The deep internationalism of both King and Malcolm is explored in many ways, including their shared reverence for Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, the era’s high profile leader of pan-Africa independence movements who was elected prime minister from a jail cell and to whom both paid visits on trips to Africa.

An economy seen to thrive on racial violence

Malcolm’s critique of capitalism is better known than King’s, due perhaps to a famous quote, “show me a capitalist and I’ll show you a blood sucker.” But in fact, economics and the causes of the disparities we decry today, were a point of convergence for the two that has similarly dimmed from today’s memory.

“They both came to define America as an empire whose political economy seemed to thrive on racial violence, exploitation of the poor, and war,” Joseph writes. In particular, King’s call in his famed Washington Mall speech demanding “a check” be cashed on behalf of Black America is largely absent from the growing reparations debate of today. So is King’s subsequent argument about the comparative injustice of two institutions, the Land Grant College Act of 1862 and the Homestead Act of the same year, with a third, Reconstruction. Both of the former transferred huge sums of public wealth to White interests and White settlers and are cherished today as examples of enlightened public policy. Some 10 percent of all the land in the United States was transferred virtually free, almost exclusively to Whites, in the late 19th Century and early 20th. That the land was first effectively seized from its indigenous residents is a distinct and separate body of crime.

The latter project of Reconstruction, meanwhile, was simply cancelled. King noted the irony that these massive public gifts to Whites were rolled out and implemented almost in tandem with the cancellations of the reparations bills and land grant promises to freed slaves made by President Abraham Lincoln.

Particularly after King’s journey to Oslo in 1964 to accept the Nobel Prize, his interest in redistributive economics grew and the divide between he and his erstwhile ally, President Lyndon Johnson, began to expand. The new Congress that was elected that year amid Johnson’s landslide would pass much of the president’s “Great Society” legislation now central to his legacy. King may have been there with Johnson to accept a pen upon signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but King in fact found it and the fuller body of reform – quite presciently in retrospect — falling far short of the scale of social change required.

“It’s historic passing set the stage for King’s transformation into a political revolutionary whose critique of American democracy found him converging with Malcolm X,” argues The Sword and the Shield.

In fact, it was during debate on part of that legislation, a filibuster in the Senate against its anti-segregation provisions, that the two leaders met for the first and only time. Given their long rivalry, some expected a clash. Far from it, the two met as comrades in arms, smiling for cameras and joking about FBI surveillance. “I’m throwing myself into the heart of the civil rights struggle,” Malcolm told King, according to one account.

Joseph notes that in this period, Malcolm was expanding his ideas about civil rights, if not tempering them. In a debate with the author and playwright Baldwin, integration was a “worthwhile goal” if it resulted in complete freedom and equality, Malcolm said. But he and the Muslim movement he represented, were not inclined to be “sitting around for another thousand years, not waiting for civil rights,” he argued in that parley.

“With that, Malcolm threw down the gauntlet that remains as central to his political legacy as it is unrecognized,” writes Joseph. “He viewed civil rights at its best as an assertion of black humanity. Not only did black lives matter, they did not require federal permission to sit at a lunch counter, the protection of troops to attend public schools, or massive demonstrations to guarantee their right to vote.” He was less interested in equality than he was in commensurate power for Black Americans. And he would be dead within a year.

The most powerful illustration of King’s transformation in the opposite direction may be Joseph’s recounting of his sermon on March 30, 1968 at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. King’s estrangement from Johnson was widening further over King’s vociferous opposition to the Vietnam War. He challenged Johnson on his commitment to anti-poverty legislation, warned that he would be leading protests at the upcoming Democrat Convention in Chicago and repeated his anti-war criticism. That night, “almost as if in response to the panoramic vision that King had laid out,” Joseph writes, Johnson went on the national airwaves to make his historic announcement that he would not seek reelection. Just days later, on April 4, King was assassinated.

And so here we are as a nation, more than 52 years later. Since then, Joseph argues, America has innovated new forms of racial oppression in criminal justice, public schools, residential segregation, and poverty that scar much of the Black community. And again the cities are erupting in protest, evocative of the uprisings a half century ago. In more than 550 cities in recent weeks, Austin included.

“There is no way to understand the history, struggle, and debate over race and democracy in contemporary America without understanding Malcolm X and Martin Luther King’s relationship to each other, to their own era and, most crucially, to our time,” The Sword and the Shield concludes. Joseph goes on to argue that the presidency of Barack Obama, while celebrated as the triumph of civil rights, has in fact framed the limits to a legislative and social response that was rejected by Malcolm X and vociferously criticized by the radical King.

“Obama’s election offered a romantic, although an unearned, conclusion to the civil rights and Black Power movements without having to examine the underside of the American dream that helped end the lives of Malcolm and Martin,” Joseph writes. “The killings of Sandra Bland, Tamira Rice, Korryn Gaines, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and Michael Brown represent only the tip of contemporary racial injustice.”

Just weeks after Joseph published those words, the grim roll grew again as George Floyd was suffocated by a policeman in Minneapolis.

Buy this book with a click to your local bookseller:If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.