Large national governments are characterizing the struggle with the coronavirus that causes this scourge, as something like a war. It is a metaphor that evokes grand mobilizations of armies headed into the teeth of war, supreme commanders poring over maps, and a home front where every shred of resource is devoted to the war abroad.

If it is something like a war, the fight with the viral adversary should be seen more as what it is – a guerilla conflict on a ubiquitous scale, where the front lines are indistinct, and the ravages of the assault are felt within our homes by those most vulnerable.

There is no one physical place where danger ends, and safety begins. No one place where a wall can be constructed, or a trench can be dug to keep out the threat. Instead, the primary theaters of operation for this crisis are dotted across the globe – our urban centers – where approximately 55 percent (and counting) of all humanity resides.

That said, we must be careful with the use of war metaphors. They can lead policy efforts astray, and amid a global pandemic, a setback anywhere is a setback everywhere.

“War metaphors can be dangerous because a war often implies a zero-sum game, characterized by an “us first” mentality,’” said Dr. Constanza Musu, a professor of International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. “In particular, the enemy in this case is not only the virus, but also can be those who spread the virus. If we are not careful about our use of such metaphors, the collaborative aspects of a so-called “war effort” can be easily lost. Instead, it is important to move from a zero-sum game to a positive-sum game.”

Though developing a positive-sum effort across international borders amid crisis is difficult to accomplish, there is reason for some optimism.

Enter two new alliances. On one flank of the battleground, the C-40 Cities – a large coalition of cities that includes Austin. On the other is a grouping so new it is not yet named – its membership including smaller states that have drawn attention for their early success: Austria, New Zealand, Singapore and five others.

Though responses will vary between urban centers and smaller countries – a coordinated strategy will be essential to overcoming the pandemic. The common imperative to create more sustainable solutions to crises, beginning with the coronavirus, should be driving these polities to collaborate. And alliances formed by polities in the shadow of powerful threats have important dimensions of history on their side.

C40 Cities Global Mayors Covid19 Recovery Task Force

On April 15th, after a virtual conference that included more than 40 mayors and other civic leaders from 25 different countries, the C40 Cities group announced the Global Mayors Covid-19 Recovery Task Force.

Head of C40 Cities and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti explained that it is city leaders which have risen amid the pandemic to act.

“Mayors are always on the front lines in the face of any challenge, and the COVID-19 crisis is no exception,” said Garcetti.

C40 Cities was started in 2005, when the Mayor of London Ken Livingstone, concerned about the threat of climate change, brought representatives together from 18 other large cities. In 2006, the number of participating cities grew to 40 and gave the organization its name. Today 96 cities, including Austin, are members.

The new Task Force is chaired by Mayor of Milan Giuseppe Sala, who oversees among the world’s hardest hit cities.

“Our immediate priority is to protect the health of our residents and overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. As we navigate the devastating daily effects of this unprecedented crisis, however, we must also look towards how we will keep our people safe in the future”, said Sala

A core belief of the C40 is that decision-making must be made with a data driven approach. From its website, “Our mayors know first-hand that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it, and we adhere to that philosophy.”

To accomplish the goals of the task force, the organization will combine academic papers, virtual conferences, and conversations with scientific leaders. From here, the group will work to develop best-practices recommendations. Through frequent virtual meetings, reports on these recommendations and how to implement them will be provided to C40 mayors.

“The coronavirus pandemic has created enormous public health and economic challenges for the world. In the weeks and months ahead, mayors will need to address many vital issues at once, including public health and safety, economic relief and recovery, and rising social service needs — all against the backdrop of climate change” explained Michael Bloomberg, the current board president.

Austrian-Led Alliance

A similarly innovative partnership to meet the challenges presented by the coronavirus pandemic, met for the first time (link in Danish) on April 24th. This alliance consists of smaller countries, led by Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, which believe they have handled the coronavirus well. The countries present were Austria, Denmark, Czech Republic, Israel, Greece, New Zealand, Singapore, and Australia.

Like the C40 Cities proposal – this new alliance will compile, analyze, and share academic reports and potential technological solutions between its members to develop effective strategies.

“The geography is very different, but they are smaller countries, smart countries,” Chancellor Kurz said.

For smaller EU states like Austria and Denmark, they may be witnessing the crisis in countries such as France, Italy, and Spain – and realize that their challenges are different, so their solutions require unique approaches to meet all facets – public health, political, economic, and social – of the crisis.

The alliance is about “how countries can best start up again, stimulate the economy and keep the virus under control at the same time,” Kurz said.

One of the goals of this new partnership, which differs slightly from the C40, is self-sufficiency in the production and distribution of personal protective equipment, medical devices, and a potential vaccine.

History

What can we expect from these burgeoning alliances of cities and smaller nation-states?

History offers some interesting lessons. Both alliances and their challenges invite comparison to earlier alliances formed by polities in the shadow of powerful threats – the Hellenic Alliance of antiquity and the Hanseatic League of the early middle ages.

The Promise of the Hellenic Alliance & The Failure of the Delian League

Fifth century B.C. Greece was an assortment of culturally similar, yet consistently at odds, city-states – including most famously Athens and Sparta. In 507 B.C., Athens sought an alliance with the greatest power of the time: the Persian Empire of Darius I.

The Athenians fundamentally misunderstood the Persian worldview. There was no tolerance for equal agreements with the King of Kings – Darius I took what he wanted – the world was a vehicle to demonstrate his greatness. When a city-state from the hinterlands asks for assistance, this meant subjugation to him.

Athenian diplomats entered into an agreement. The Athenian aristocracy believed it beneath their dignity, rejected the pact, and never bothered to inform the Persians. Athens thought of itself as independent, and Darius I believed Athens his subordinate

A few years later in 499 B.C., several Persian-controlled Greek city-states in Ionia rebelled. Athens voted to assist, and Athenian troops burned Sardis, the center of regional Persian control. Despite quelling the rebellion, Darius I was enraged that the Athenians assisted the revolt. They were supposed to be his subordinates. He vowed revenge.

Greek cities now faced an existential threat. The Persians would be unmoved by the squabbles between them. For those who opposed them, the Persians were an insuppressible and unforgiving force of history. Like the Medians and the Babylonians before them, observers of the time expected the Greeks to be wiped out. Yet Greek culture and ideas from that time persist today and are central to many modern societies. How was this possible?

Recent popular culture paints a picture of overcoming long odds, centered on the Spartan military resolve at Thermopylae in the 1998 book Gates of Fire and the 2007 movie 300.

But the story goes beyond just one of history’s greatest upsets. The real story is one of an alliance, established to defeat the Persian invasion, between cities with many differences to defeat a common threat. And it is this story that is so relevant to our global fight today against COVID-19.

Known to history as the Hellenic Alliance, the success of this alliance depended on the rivalry between Athens and Sparta to be put aside, and 31 city-states to collectively act to survive.

The efforts of the Hellenic Alliance shocked the world in which they existed. The Athenians abandoned their city to Persian sack. The Spartans sacrificed many troops including their King Leonidas. None of the 31 city-states gave in to surrender or peace with the Persians. The invasion was repelled.

The alliance was not successful long term. After the war, Sparta left the alliance, believing the threat extinguished. By 454 B.C., renamed the Delian League, the alliance served as a coercive instrument of empire for Athens. Attempts to secede were met with brutality, and Athenian abuse resulted in the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.

The fractures caused by the collapse of the Delian League left Greece open to conquest from Macedonia, and later Rome – as the city-states never again managed to unify as they did against the Persians.

Was it inevitable that collaboration between the cities was temporary? Maybe. But the people of Athens, Sparta, and the other members of the League did not have the benefit of themselves as historical examples. We do.

When the C40 Cities and the small country alliance defeat the coronavirus, their Persian Empire, can they maintain the collaboration needed to defeat their Macedonians? What about their Romans?

Hanseatic League

Like 5th century B.C. Greece, power in the Baltic Sea in 1250 A.D. was fractionated among city-states.

Many nearby powers – including England, Denmark, Sweden – competed with the cities and benefitted from having extensive territory and centralized monarchies to protect their merchants and sustain their presence.

A few of the cities did something incredibly unique for the time to respond – they formed a trading association and alliance to benefit their mutual interests.

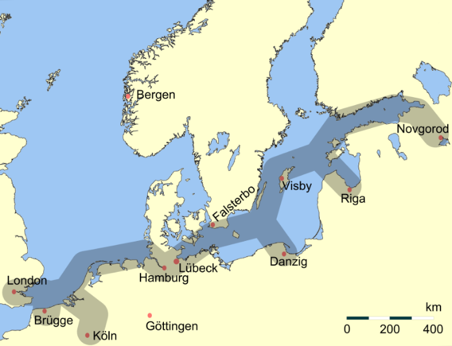

Starting in 1241 with the founding cities of Lübeck and Hamburg, the association quickly grew. Important cities including Cologne, Bremen, Riga, Reval (Tallinn), and others joined during the next century.

By 1356 these cities established the Hanseatic League. Coming from the German word Hanse, meaning “crowd” or “community,” the cities and their merchants would freely associate themselves under the authority of the Hanseatic Diet. The cities would collaborate on mutual defense, legal structure, and trade expansion.

In 1360, the Hanseatic League would be tested. King Valdemar IV of Denmark, attempting to re-assert Danish hegemony of the region, determined to disrupt growing Hanseatic influence.

In 1370, Denmark was forced into the Treaty of Stralsund. The treaty guaranteed that the Hanseatic League would have free access to all Danish-controlled land and sea – ushering in a golden age for the merchants of the League.

Member cities came together from many different backgrounds to form the Hanseatic League. The need for cooperation and defense outweighed those differences, and they successfully maintained collaboration.

Stretching from the Russian city of Novgorod, through the Baltic and North Seas, extending to London– the Hanseatic League controlled regional trade for 300 years.

Critical to their success was the development of the Kontor system. Meaning “office”, Kontors were League-owned trading posts typically operating in cities outside of League membership. Kontors ensured that the League maintained an active presence in many cities and allowed the League to rapidly respond to challenges across a large region with consistency.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic – perhaps there is potential for virtual Kontors of sorts? A virtual Kontor could serve as a place to communicate and compare ideas with other cities. The long-term viability of these alliances requires structures of collaboration that have true staying power and the Hanseatic Kontor is one potential model.

Concluding Thoughts

From our two historical examples, we see that cooperation between smaller powers against a large threat delivers strength in numbers and is useful for putting differences of the past on hold. But the cooperation must continue after the crisis passes and structures of collaboration must be maintained.

Excessively affected by the pandemic, global cities are getting a preview for what is likely to come because of climate change. Terrible and costly as it is, this crisis is merely a dress rehearsal.

If the fight against the coronavirus really is something like a war, then our definition of war must change. A sustainable, global, positive-sum approach might seem idealistic, but these emerging partnerships of cities and smaller countries offer at least a glimmer of hope. The earlier these networks of alliances begin, the stronger their foundations, and the more robust our commitment – the better prepared they will be to tackle whatever the future may bring.

If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.