A dozen years ago, when I was a newly minted CEO, still running my business out of the Austin Technology Incubator, I was visited by a representative from the city to get my feedback on the emergency services that the city provided. I expressed my general satisfaction with the fire department and EMS, but dissatisfaction with the police. While it was not a critique of the Austin Police Department, or APD, in particular as opposed to other police departments, I felt that our city’s police were particularly aggressive.

It was 2009, and they had just initiated a campaign of entering bars downtown and arresting individuals for public intoxication. In fact, in the five years that followed, that specific charge, one of the more subjective crimes on the books, represented 10 percent of arrests in Austin. According to Texas law, one is guilty, “if the person appears in a public place while intoxicated to the degree that the person may endanger the person or another.” This puts police’s subjectivity at the core of their job. It forces officers to focus on those individuals or groups that they choose, which is most often blacks and other minorities. This is little different than my native New Jersey’s well-publicized racial profiling of African Americans on its highways a decade earlier. In both cases, routine use of subjective reasons to conduct otherwise warrantless searches of targeted minorities will result in higher arrest rates, for a range of crimes, for those groups; even if the underlying rate of law-breaking is no different. That in turn, further justifies continued profiling, which continues the cycle of systemic racism.

I was less concerned about public intoxication laws than the fact that there were simply too many, often vague, criminal laws on the books being subjectively enforced. That fact leads to most citizens potentially breaking at least a law at almost all times while it puts officers in a position where they can choose how and when to enforce it. It’s the reason that in this country, the first reaction when one sees a police officer on the highway or walks past them on the street is not, “I feel safe because of our law enforcement,” but instead, “what might I have done wrong?” Those are the thoughts that one should have in an occupied territory, or a repressive totalitarian regime, not in one of the world’s founding democracies.

This situation gives police both the power to choose how to enforce the laws and to decide against whom they will enforce those same laws.

The self-fulfilling prophecy of minority arrests for victimless crimes

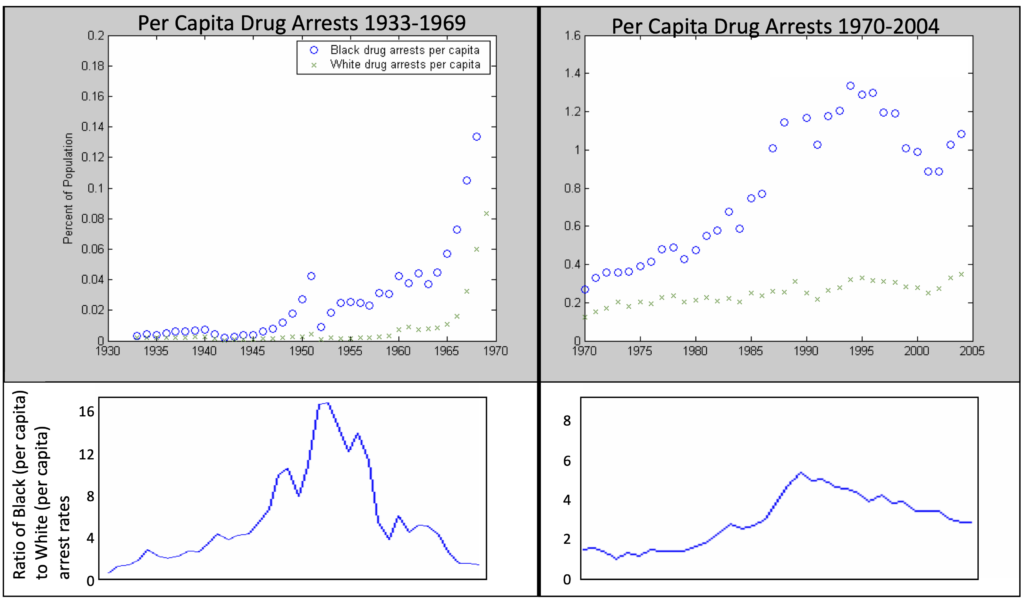

A year earlier, I had co-authored a paper titled “Divergence Followed by Convergence: The Propagation of Arrest Rates in Victimless Crimes” in which we looked at the FBI’s Uniform Crime Statistics for data on this exact topic. In victimless crimes, there is not a dead body or a battered victim that triggers the launch. With no victim or complainant, these arrests are a function of a police department’s priorities and focus. When police believe that minorities commit crimes at a higher rate, they will find more crimes amongst those groups. As we found in the data for both drug and prostitution arrests, there is a clear self-fulfilling prophesy.

While one can debate the actual rates of these “crimes” in both populations (the data suggests that they are identical), it is clear that at various points over the last century, external factors caused a disproportionate spike in the number of African Americans arrested for these victimless crimes as compared to their white counterparts. And each time this occurred, it created biases that took decades to dissipate, if ever. Each time that large amounts of money were put towards an effort to get tough on crime, like the 1994 Crime Bill, those existing biases would be exacerbated, and the cycle would restart again. And with 65% of Austin’s budget currently allocated to “public safety,” it is difficult to argue that there is not at least an implicit effort to be tough on crime in almost every city across the nation.

I gave the city official with whom I was discussing this issue the simple example of jaywalking. Everyone does it, it’s impossible to actually prevent, and therefore it shouldn’t be a crime. Otherwise, it gives the police cause to stop nearly anyone. Racism and bias aside, a more clearly defined, and a consistently enforced list of offenses would allow people to better understand what they can and cannot do and, I would argue, there would be better adherence to that shorter list of statutes. Without that, citizens are forced to make their own evaluation of a law’s importance, or the likelihood of enforcement, and our legal system becomes a set of guideposts as opposed to rules.

This isn’t just a liberal talking point. Even former Texas Governor Rick Perry has pushed for criminal justice reform, once stating: “You want to talk about real conservative governance, shut a prison down.”

My interviewer shifted from puzzled to responsive and was happy to mention that the newly installed Police Chief Acevedo, now heading the Houston Police Department, held similar beliefs and had recently given a speech stating that he was going to fully enforce all laws. Jaywalking included. I quickly gave up and ended the conversation. Unsurprisingly, that was the last time I was visited by the city.

That was a lifetime ago. Before my hair grew out or beard grew in. Before Ferguson and Tamir Rice. Before Black Lives Matter and George Floyd. And even then, as a clean-cut, business-owning, white male, the most protected class in this country, my instinctive reaction upon seeing the police always had, and still has, a tint of fear. I cannot even begin to imagine how a black man must feel.

Today, our cities are on fire, quite literally. Nothing about the situation has changed; just the quality of cell phone cameras. Even post “stop-and-frisk,” broad, overreaching laws have allowed the police to reinforce their own biases and violate the rights of minorities. And it’s not just about the police’s brutality. It’s about the disproportionate numbers of minorities crowding our prison systems. African Americans in particular are impacted. One in four black males will be put through the criminal justice system in their lifetime. Latino immigrants are locked up in Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, detention facilities and deported for “crimes” that a white man would never get stopped for. I’ve seen a broken taillight uncover an expired driver’s license and lead to a father spending a month in an ICE detention facility hundreds of miles from his wife and children. With those numbers, of course the police are focused on minorities. The legal system has reinforced the police’s own predisposed beliefs. It is the definition of a self-fulfilling prophesy.

Police abuse is the most treasonous crime in society and must be punished as such

As a result, protests are going on in Austin over the overreaching use of power and force by the police while Minneapolis, Atlanta, Dallas, Des Moines, Detroit, Los Angeles and others are erupting in more violent protests and rioting. The laws favor the police. Evading arrest is a crime, even if there is no associated charge for arrest. Assaulting a police officer carries higher criminal penalties than assaulting another citizen. But the penalties for an officer abusing the rights of a citizen, even killing them, appear to be essentially non-existent. As a society we bestow upon the police the legitimate use of power to protect us. They can shoot, interrogate, and imprison. That would be murder, torture, and kidnapping if it were done by an average citizen. Like a father abusing his own child, the abuse of that power is such a fundamental betrayal of the public trust that it must be considered the most treasonous crime in our society and punished as such.

Our country needs to change. The numbers are astounding. The racism is clear. The inability to improve through internal means is even clearer. Conversations and demonstrations haven’t changed matters in the six years since Ferguson, the twenty-eight years since Rodney King, or the eighty-seven years since the FBI began collecting crime statistics. We shouldn’t be surprised when our cities, Austin included, end up engulfed in flames.

If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.